Black Las Vegas fathers share lessons they learned from their dads

Black Las Vegas fathers share lessons they learned from their dads

June 19, 2020

By Christopher Lawrence Las Vegas Review-Journal

As much as we love our dads, Father’s Day has always been an afterthought.

Mom gets a day filled with brunches and flowers and fawning. Dad’s lucky if he gets a tie and a couple of minutes of alone time.

Father’s Day wasn’t even officially recognized as a permanent national holiday until 1972 — some 58 years after Woodrow Wilson set aside Mother’s Day.

Many African American fathers, though, have gotten used to having their accomplishments overlooked. Over the years, a certain stigma or dismissiveness has become attached to Black fatherhood.

With that in mind, we reached out to some prominent Black Las Vegans to ask about the best lessons they took from their fathers, most of which they’ve been able to pass on to their own children.

‘It has always been a collective effort’

Anything you’d want to know about Black fatherhood, Javon Johnson can tell you, even though his first child isn’t due to be born for a little more than a month.

Just say the words “Black fatherhood,” and the director of African American and African Diaspora Studies at UNLV will take you on a rapid-fire journey of more than a century of slights, from the post-emancipation worries about “the Negro problem” up through the crack epidemic, mass incarceration and the exporting of the industrial jobs upon which many Black men once relied.

“It became, ‘Black men can’t hold jobs.’ We don’t talk about the shifting economies that took jobs,” he says. “This creates the narrative that Black fathers, because masculinity was tied to your ability to be a breadwinner, are inherently not capable of being fathers.”

Johnson, 39, knew better at an early age.

“What I know to be true about Black fatherhood is that it has always been a collective effort,” he says. “My uncles raised me. The pastor at the church also was a father to me. In addition to my football coach, in addition to my basketball coach, in addition to my actual stepfather, who actually raised me. For me, it’s really important to name that collective group because of how they all played huge roles.”

Those uncles would alternate picking him up from school and taking him to and from practices. His football coach would attend his parent-teacher nights.

When Johnson was a 13-year-old football player in Los Angeles, his team had lost only two games over the span of five years. Then it got cocky and lost its third.

“I was angry, and I wanted to fight, and I balled my fists up,” Johnson recalls.

He was approaching members of the other team when his stepfather, Foster Mijares, intervened and walked him to their car.

“He crouched down and said, ‘I know this one hurts. Cry it out if you have to. But you’ve gotta keep your head up. You’ve gotta figure out a way to get them the next time.’ That simple moment was the first time, at 13 years old, that somebody told me that I could cry.”

The effect was profound. As part of a military family, Johnson’s uncles, as kind as they were to him, had driven home the point that he was never supposed to shed a tear.

“What that lesson taught me is that masculine love and Black fatherhood is one of tenderness, one of care, one of holding the way someone needs to be held. … You don’t always have to be rough and rugged, but that we, too, can have soft moments.”

Once his daughter is born, Johnson will have that knowledge in his skill set.

“I want to also father with the sense of care of that very moment. That, ‘It’s OK. I’m here. We’ll figure out how to get ’em next time.’ ”

The talk passed down through generations

“It’s unfortunate that the main advice that I received from my father and then I gave my sons as well, who are all young adults now, is about how to conduct themselves if they’re pulled over by the police,” says Craig Knight, general manager of KCEP-FM, 88.1, better known as Power 88.

His father, Merald “Bubba” Knight of Gladys Knight & the Pips fame, gave him that talk. He’s given it to his two sons, two daughters and two stepsons. One day soon, he’ll give it to his three grandchildren, all of whom are under age 12.

“It’s the same talk that passes down through generations,” Knight attests.

Essentially, it goes like this. If you’re pulled over, roll down all your windows so the officers can see inside. Have your license and registration in your hands, and have those hands on the steering wheel at 10 and 2. Refer to the officers as “Sir” or “Ma’am.” Listen. Don’t argue. Stay calm. And, above all else, don’t make any sudden movements.

Unlike “the talk” many fathers have, the one about the birds and the bees, Knight, 55, doesn’t have this conversation just once.

“In this case, we’ve had the talk again, the refresher, because of everything that’s been happening,” he says. “And then we had the talk also about how to properly protest. How to protect yourself. Be aware of your surroundings. Stay in groups. Stay away from the agitators. Stay as peaceful as possible. And just be alert at all times.”

With Black men being found hanged from trees in recent days, Knight is having to ask his children, ages 22 to 37, not to travel anywhere alone and not to walk through strange neighborhoods. “Now we’re back to that again,” he says with a sigh.

One son, Raven, still lives at home. He works the night shift and gets home around 5:30 a.m. Knight and his wife, Nicole, don’t sleep much until then.

“We’re praying that he’s not pulled over. We’re praying that he doesn’t have a flat or his car (doesn’t) break down somewhere. So when we hear him come in and the alarm goes off, we’re, like, ‘Whew, now we can go to sleep for a few hours.’ ”

They tried always to walk with pride

Whether it was his father, Larry, who worked in the produce department of a grocery store in his native Dallas, or his stepfather, Jonas Claiborne, a technician at Texas Instruments, Nevada Attorney General Aaron Ford looked to them to see how to carry himself.

“Just the perceptions that people sometimes draw and place upon you is something that was communicated to me, nonverbally, just by the way that they interacted with folks and by the way that they tried to always walk with pride and engage with pride and be unabashedly unintimidated.”

Now that Ford, 48, and his wife, Berna, are raising three sons — Avery, Aaron II and Alexander — as well as their nephew, Devin, he makes sure they’re never unaware that they are examples. How they act has ramifications that reach way beyond themselves. All it takes is one misstep to have someone write them off as how they, the family, African Americans or Americans in general always behave.

“If you were to ask my sons who they represent, they would say, ‘I represent myself, the Ford name, African Americans and our country,’ ” Ford says. “It’s a blessing to be able to do that but also, sometimes, an unfair burden. It’s something I think that is at the forefront of my sons’ and my nephew’s minds at all times when they try to interact.”

As for the burden part of that equation, he admits it can be hard when “you have to shoulder the entirety of your race or your identity through your actions and interactions with other folks, and through your activities and through your accomplishments or failures.”

That message of representation stuck with his sons and nephew, Ford says, because it’s been reinforced, early and often.

“I’ve told them, point blank, on several occasions and reminded them beyond that. It’s funny, because this morning I was talking to my oldest son, and he said, on his own volition, ‘I remember who I represent.’ … It made me smile, because it’s a reflection of conversations that we’ve had over the course of time.”

Communities must come together to prosper

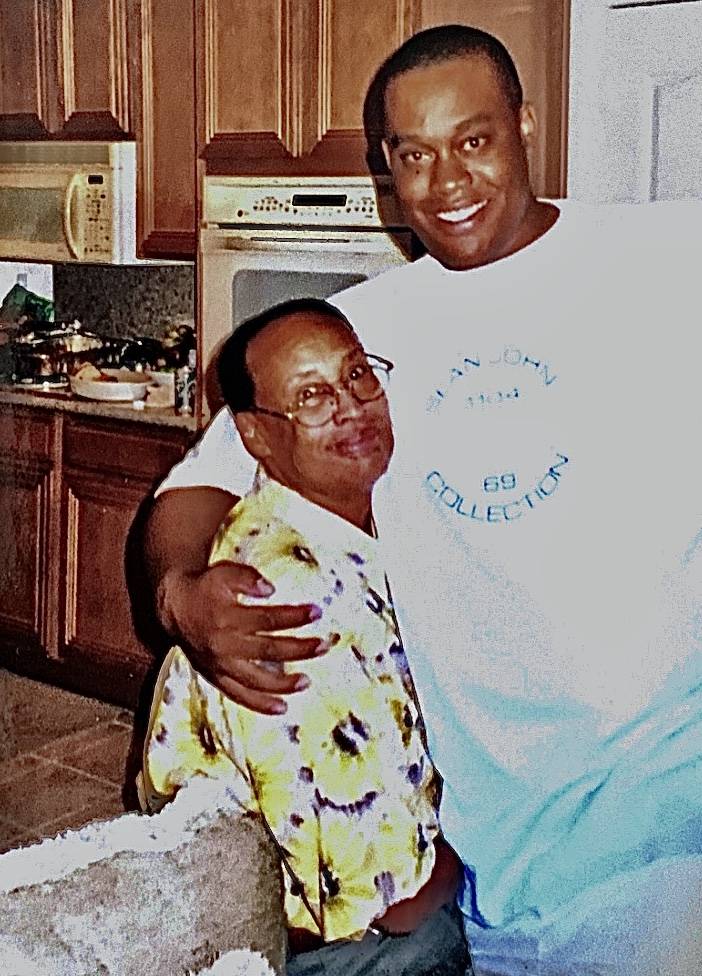

As a young man working part time in his father’s office, keeping track of what people owed when they weren’t able to pay for that day’s visit, Las Vegas Councilman Cedric Crear learned by example.

Dr. John Crear was just the second Black physician in Nevada, and he was never not busy. House calls. Random knocks on the door of his home from neighbors seeking help. If patients were ill, he’d take them food.

“He went out and worked every day,” Crear, 50, recalls. “He was a community servant. He gave away more free medical care than he took in for payment.”

A loose barter system emerged, with Dr. Crear’s patients helping out whenever he needed home or car repair in the Historic Westside.

“I’m a product of my environment,” Crear says. “I’m a product of living in my community, being raised in my community and seeing how communities need to come together in order to prosper.”

Not content to pass that message down to just his daughters, Hagan and Kennedy, he’s spreading the word through mentorships and his Civic Engagement Day program. Since he began representing Ward 5 in 2018, Crear has welcomed more than 250 young constituents to City Hall, given them tours, bought them lunch and let them sit in on meetings. The program’s goal is to give the participants a vision of a better future.

“I always say this, whether I was in office or not, I would still be engaged in my community,” Crear says. “I just have a different platform that I’m able to execute on, which is powerful.”

‘Hard work will always persevere’

The value of hard work was never far from Ronnie Rainwater’s biracial childhood home in Norwalk, California.

He’d watch his white father, also named Ronnie, leave for his job as a hospital cook every day at 3 or 4 a.m., despite his dad being legally blind. His African American mother, Sharon, is legally blind as well.

“I just saw that, in order to support his family, he never really let his handicap get in the way. That’s something that I saw at a very young age.”

Rainwater’s first official job, at 16, was as a pot washer in that hospital. After having spent 20 years working his way up the ranks at Delmonico Steakhouse at The Venetian, Rainwater, 44, was recently promoted to director of culinary operations overseeing Emeril Lagasse’s three Las Vegas restaurants.

His actual first job, washing buses for his uncle, who had a contract with the Los Angeles Unified School District, came when he was 13. He’d work 12- to 14-hour shifts because he realized if he wanted nice things, he’d have to pay for them himself.

“I would take my weekends, which, as a 13-year-old kid, were valuable,” Rainwater recalls. “You went to school during the week, and you wanted to hang out on the weekends. So I would sacrifice that and work, because during the week I had the most lunch money and (the best) snack time. I bought my first pair of Air Jordans with that money.”

Rainwater may not have had a Black father, but he’s relying on the lessons he’s learned now that he’s become one himself. His daughter, Riley, is about to turn 16. His son, Regan, just turned 13.

“I’ve tried to instill that in my kids, that regardless of whatever personal challenges or circumstances you have, or limitations you think you have, hard work will always persevere. You may not be the most talented person in the room, but you can outwork a more talented person.”